Self-organization of tissue

Self-organization is the spontaneous formation of overall ordered patterns and structures from the local interactions of elements in a population that have minimal patterns. Self-organization is often associated with emergence - the spontaneous appearance of an ordered property of the whole that cannot be explained by the sum of its elements.

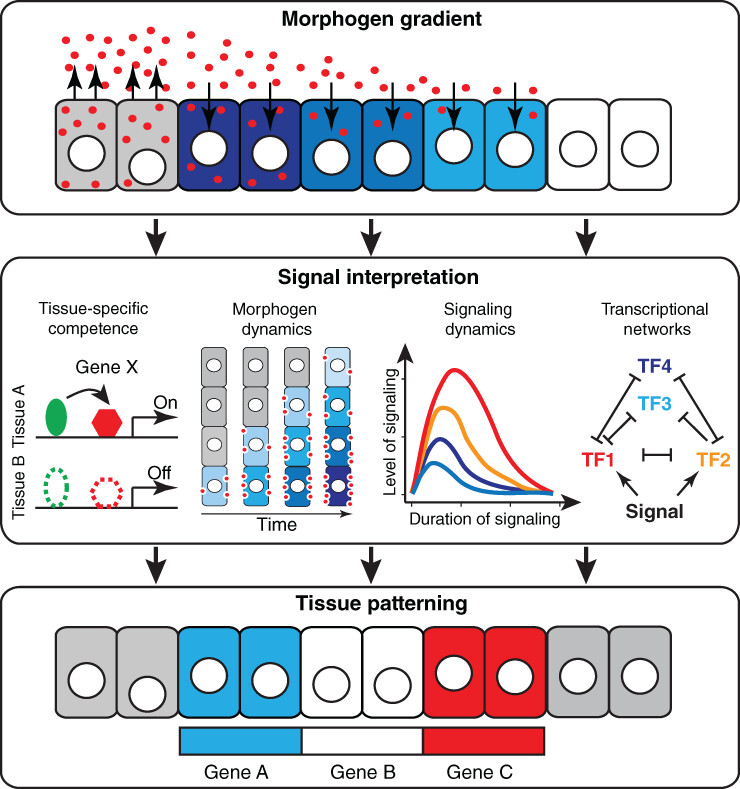

Anyone familiar with developmental biology is probably comfortable with the idea of cytokine gradients and symmetry breaking. That cells can radically change along the axes of the chemical gradients that change in a distance-sensitive fashion.

Cytokines are signaling molecules that are secreted by one cell to have an effect on another cell. Cytokine gradients are formed due to a diffusion gradient. The cytokine is found in greater concentration the more close to the release cell and decreases with distance. Different cells can respond more/less to specific concentrations of the cytokine, which elicit different effects. Also known as a morphogen gradient

In biology, tissue self-organization, unlike non-living matter, involve stigmergy - a history dependency. This causes rules of interactions between elements to be dynamic and evolve in time and space in a history-dependent manner.

source: 10.1002/wdev.271

There are three categories of tissue self-organization:

- Self-assembly

- Self-patterning

- Self-morphogenesis

These three occur concurrently during development and are not necessarily independent of each other.

Self-assembly is time-evolving control of relative cellular positions due to local rules. Cells move relative to each other based on their local environment. The rules can be simple or complex.

Self-Patterning is the spatiotemporal control of cell status by local rules without external cues. Self-assembly can contribute to this. This explains how complex tissue patterns spontaneously appear from homogenous cell populations.

The most common example of self-patterning in developmental biology is symmetry breaking. Often the result of stochastic processes that are stabilized by intercellular mechanisms, e.g., the sperm entry point on the egg determines a break in symmetry.

As you get more self-patterning, new directional biochemical gradients and newly activated regulatory networks form, which permit further local rules for patterning. While these axes are forming, the clump of patterned cells begin to take on shape via morphogenesis.

Self-driven morphogenesis is spatiotemporal control of intrinsic tissue mechanisms. This occurs in absence of external forces and spatial constraints. Involves complex control of locally generated internal cascades that dynamically modify cell morphology (e.g., for cell migration).

Observing individual cells, their behaviours are complex but quite stochastic due to extrinsic and intrinsic fluctuations. Nonetheless, as a whole, cells in a system work together to determine the pattern, shape, size, and movement of their society.

It’s clear that multicellular systems involve numerous regulatory components and the complexity of these interactions are beyond comprehension. These highly robust phenotypes would be difficult to be explained by rigid control of the regulatory components. Instead, perhaps there are only a limited number of control states (i.e., epigenetic attractors) that allow flexible dynamics to permit multicellularity. Identifying constraints for dynamics could reveal more about what a system can do than rigid rules currently do.

To read more about flexibility to rigid rules check out this post

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: