Art is a way to take a snapshot of consciousness

For me, that is where the beauty comes from. Being able to peer into the mind of an artist’s subjective experience. We all like to think we experience the world the same, but art is evidence that we do not.

I think it’s easy to dismiss certain arts as garbage, especially if it’s something that feels alien to us. But being able to understand the artist’s attempt to capture what they experience gives us a clue in how their mind works and is itself another form of beauty.

Daniel Tammet has Asperger’s syndrome (a form of high-functioning autism spectrum disorder; ASD), as well as savant syndrome. He possesses undreamed of numerical and linguistic abilities. He is unique as a savant because he has well-developed social skills.

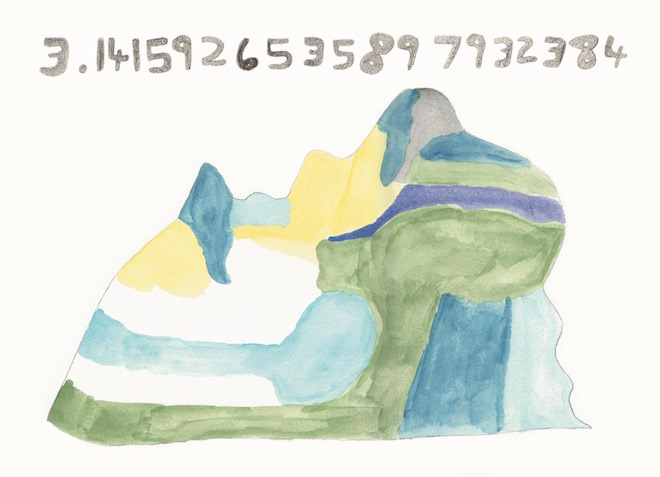

People with ASD sometimes have synesthesia, a condition where sensory and cognitive pathways are interlinked. For Daniel Tammet, he is able to see words as colours and numbers as not only colours but also in different shapes and sizes. A great example of this is when he describes the number pi (i.e., 3.141592653…) He sees the decimals of pi as mountain landscapes consisting of a series of differently coloured numbers. While I struggle to see how this picture resembles pi, I am in awe that such an experience goes on in his head.

source: Daniel Tammet

Another great example is Dr. P described in Oliver Sacks’ “The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat”. Dr. P, a patient of Oliver Sacks, was diagnosed with a case of total visual agnosia - a condition where the patient can see but cannot recognize or interpret visual information. Specifically, Dr. P had an inability to represent objects with multiple parts as well as trouble representing parts of objects. He would often mistake inanimate objects for people and struggled to recognizing people by their face.

Typically, when we recognize someone, we look at their face as a whole. Dr. P could no longer do this and had learned to compensate by analyzing specific features of the person, recognize people by their nose or their hair. This inability to perceive more than one object at a time, and thus unable to form a whole understanding was not limited to faces but most of his visual system. He was “lost in a world of lifeless abstractions”. What was absolutely perplexing was that he was completely unaware of his problem.

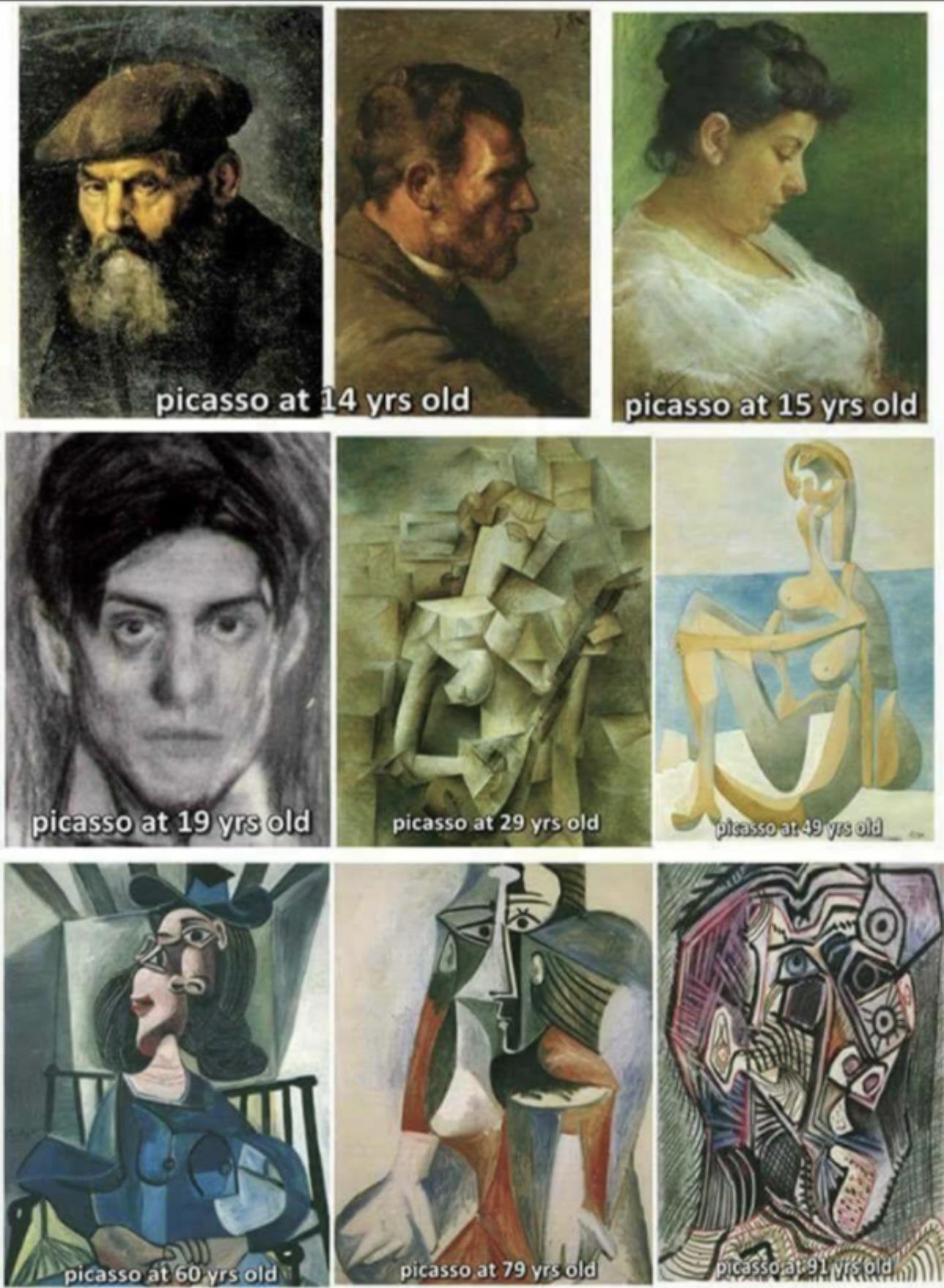

The reason why I bring up Dr. P is Oliver Sacks noticed something. Dr. P was a lifelong painter. He painted before his disease and into his disease. As Oliver Sacks walked past them in chronological order, what he saw first was naturalistic and realism with incredibly detail and concrete. Continuing, years later the paintings became less naturalistic and detailed, but far more abstract, even geometrical/cubist. In the final paintings, his art began resembling nonsense with mere chaotic lines and blotches of paint.

Despite this spiral into more abstract representations of visual information with the inability to form a coherent painting in his mind’s eye, Dr. P was still able to function relatively normal. How? Dr. P, a gifted painter as well as a singer, had to turn everything into a song. If disrupted, he’d completely stop and would be unable to identify his own body or clothes. He needed to distract his distorted higher-level system while his low-level vision could still interact with other processes to allow him to be functional. A case of hierarchal interconnectivity.

What I find mystifying is Dr. P’s artistic progression through his life followed a similar progression of Picasso. Makes you wonder what might have been going on in Picasso’s brain.

source: A Reddit Post

Dr. P’s story is a tragically beautiful case of pairting artistic style to stages of a neurological disorder. From realism to non-representational and finally abstract, “the paintings were a tragic pathological exhibit, which belonged to neurology, not art.”

How much of art is just a reflection of the artist’s pathological development? Perhaps not pathological but just a standard deviation or 3 away from the norm.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: